Voices Unlocked: The Power of Puppetry

In March 2017, I was attempting to determine what a first grader with autism needed as he was incoherently perseverating on an event. My prompts to have him slow down or to redirect his obsession failed. I attempted another half dozen interventions, but he was not responsive. In a final bid to support this student, I reached for a stuffed animal gorilla in my classroom, who had been mistakenly named Mr. Monkey. I held him up and began amateur ventriloquism; the gorilla ask similar questions, but the student’s entire physical and emotional presence de-escalated. Mr. Monkey and the first grader had the most sophisticated and insightful conversation I had witnessed from the student all year.

Other students in the class approached Mr. Monkey and began to ask questions and make detailed observations. I was thrilled with the spontaneously complex discussions Mr. Monkey and the students were having as increasing the level of student to student discourse has been a school-wide goal and is an area of personal professional growth. I planned puppet-making and puppetry as the next unit for the first and second grade as I wanted to give all students the opportunity to have uninhibited conversations with a puppet.

As the K-8th grade visual art teacher at Gardner Pilot Academy (GPA), I have the joy of teaching 400 students a week. The majority of our students are English Language Learners, and as a full-inclusion Boston Public School, approximately 25 percent of our student body has an identified disability. Beyond these characteristics, there are a variety of curricular barriers that sometimes inhibit student talk. Students in my first and second-grade art classes had typically been engaging in single word or simple sentence responses to questions. Within a conversation, most students either lacked the skills to participate in a complex discussion or were conversationally timid. The puppetry unit gave them the means for communicating with confidence as well as a format for practicing story telling.

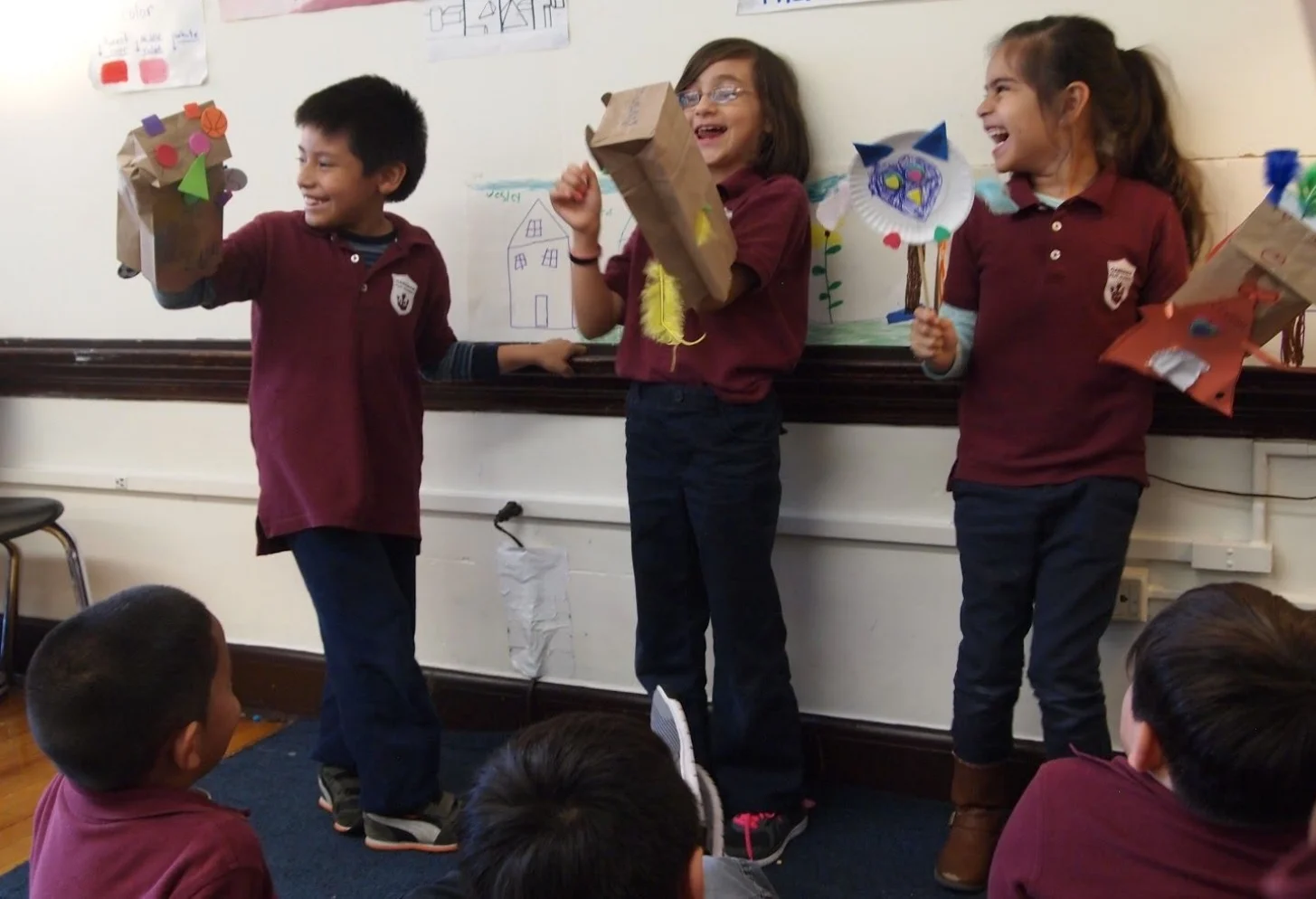

The unit began with a class on planning their puppets. Students then had several classes to self-select materials to design a puppet. We reviewed story elements using multiple means of representation and students created a set, plot, and dialogue for their story. Presenting their stories was optional, but 100 percent of students were eager to share their art and speak in front of the class.

Puppets were a catalyst for learning about storytelling and the art of puppet making. More importantly, my students were taking conversational risks, growing their vocabularies, and authentically practicing sustained discourse. We used the puppets as a means of communication for the remainder of the year, as the positive influence of the puppets extended far beyond the end of the unit.

Liz Byron teaches at Boston's Gardner Pilot Academy.